two sisters

the story of my mother gertrud and her sister hildegund

This is the story of two sisters, Hildegund and Gertrud Becker, as it was related to me by them and as I remember the latter part myself, when I was taking care of them from 2005 to 2019.

(click on “+” to open the chapters)

childhood

Their parents Josef Becker and Frieda Biner married after World War I and lived in Aschaffenburg in Germany. Josef worked as a teacher in the local primary school. He had lost a leg in WWI, but with an artificial limb and a walking stick he was able to walk around without help.

On August 14, 1922, Hildegund was born as their first child. On May 14, 1925, the second daughter, Gertrud, followed and in 1927 their brother Wolfgang was born. Already as children Hildegund and Gertrud were often playing together.

All three grew up in Aschaffenburg and went to school there. In 1933, when the Nazis took over the government, the Beckers were living a fairly normal middle class family life. The next picture shows the family celebrating May 1, 1933 (labor day). I don’t know why dad looks so grumpy and mom so frustrated, but the three children seem to be joyful and unimpressed by their parents’ mood.

The kids obviously enjoyed masquerading for carnival in the same year:

During summer of that same year, we see Josef holding proudly his motorized Sachs bicycle, which allowed him to tour the vicinity without having to pedal. He had a special construction that enabled him to control the vehicle with one leg. He could take one of the kids on the back and they loved to ride with him.

Those were the happy days and little did they suspect then about the calamities and suffering that came upon the family and upon so many million people during the following fifteen years.

wartime

The next picture is from 1944. Around this time Hildegund started to study classical singing in Dresden. Gertrud and Wolfgang were still going to school. Wolfgang is wearing a uniform. In the final two years of WWII the older school boys had to help with defending the country by joining the Flak-artillery. These combat units were equipped with special cannons (Flak) to bring down attacking bombers during air raids.

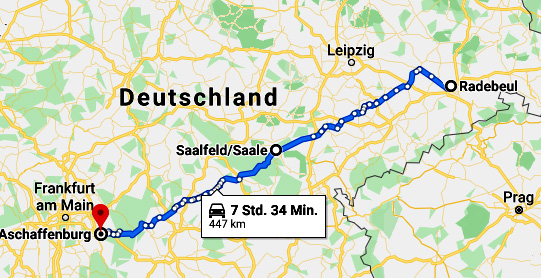

While the boys were marching to the collapsing front lines, the girls had to spend their holidays in Reichsarbeitsdienst (RAD) doing unpaid work in factories or on farms. (The next picture is retrieved from the internet, showing marching soldiers and young women doing farm work). In February 1945 Gertrud had joined the RAD camp in Radebeul, a small town close to Dresden. Whenever possible she would visit her sister who lived in a small room in downtown Dresden.

In the night of February 13 to 14 the heaviest air raid on a city in the Second World War was carried out on Dresden (approximately 630,000 inhabitants). 773 British bombers dropped massive amounts of explosive bombs in two waves. With a lot of roofs and windows destroyed by the detonations, the 650,000 subsequently dropped incendiary bombs could have a greater impact. The firestorm destroyed about 80,000 homes, and its heat deformed all the glass in the downtown area. The British night attack on the unprotected city, which had no air defense, was followed by the carpet bombing by 311 American planes during the day.

On February 15, the already completely destroyed Dresden, which was overcrowded with Silesian refugees, faced another attack by the US Air Force. Altogether up to 25,000 people lost their lives. Many bodies, charred beyond recognition, lay for days on the road or in the rubble before the piles of corpses could be burned to prevent epidemics. (translated from https://www.dhm.de/lemo/kapitel/der-zweite-weltkrieg/kriegsverlauf/bombardierung-von-dresden-1945.html)

From the camp in Radebeul Gertrud and the other workers could see the fire and smoke, hear the noise of the detonations and, as she herself said to me “smell the odor of fried meat”. Naturally she was terribly frightened that her sister would not survive this hellish inferno and she wanted to search for her on the next morning. But the leaders of the camp didn’t allow anybody to leave the camp before the 15th or 16th because the air raids were still continuing. When she finally was allowed to walk into the city, she found the house, where Hildegund had stayed, destroyed. The basement, which was the regular air raid shelter, was still smoldering hot. Frantically Gertrud started searching and calling her sister amid the ruins, corpses and straying people, and finally found her in a state of total shock. She had lost her voice and had difficulties finding her orientation. Later she remembered that during the bombing she and the other inhabitants had stayed in the air raid shelter underneath the house. Some smoke had entered the chambers in the basement and she must have fallen unconscious. When people sought for survivors afterwards, they thought that Hildegund was dead and threw her on the pile with the corpses. But she did regain consciousness and managed to pull herself up and walk away from the horrible heap of dead bodies. Considering that temperatures in February in Germany are usually around freezing point, it’s a miracle that Hildegund survived. In spite of the nightmarish setting the sisters were overjoyed to be reunited and made their way back to the camp in Radebeul, where Hildegund could recover a little bit.

However, soon they were told to leave the camp, as refugees from the east front needed the space. Most railroads had been destroyed through the bombings. So they worked their way on foot and by hitchhiking to a small town about 200 km westward of Radebeul. In Saalfeld their uncle Hans, a catholic priest, was head of the local parish and provided them with food and shelter for some weeks.

The young women wanted to reunite with their parents and their brother in Aschaffenburg and – as no telephone communication was possible and letters were only transported irregularly – they decided to continue their journey after a few weeks on the off chance. It would be even more adventurous than the first half of the trip. A German ammunition truck gave them a lift, but when allied hedgehoppers were looming over their heads trying to destroy the remaining traffic infrastructure, they risked being blown into pieces. The American planes were equipped with machine guns and diving so low, that the pilots could be seen from the ground.

The driver managed to camouflage his truck. He and the young women hid in a ditch until the attack was over and fortunately they were able to continue the journey to Aschaffenburg.

In the meantime, unbeknown to Gertrud and Hildegund, the house of their parents had been damaged during a bomb attack on Aschaffenburg. Josef and Frieda had found a temporary home with friends in a village close to Aschaffenburg, called Hösbach. Incidentally the ammunition truck’s route passed through this village and Frieda happened to walk along the main road at the same time and spotted her two daughters in the driver’s cab. The miraculously reunited family stayed in Hösbach until the end of the war on May 7, 1945. In spite of the horrors and fears they had gone through, the Beckers considered themselves lucky that all five of them had survived, while most families had lost one or more members.

In the sixties, when my mom told me her stories from the war for the first time, she said once “There was a beauty about war, there were no worries about the future possible, because we never knew what would happen tomorrow”.

marriages and careers

After the war Hildegund, whose voice had returned, continued her studies of classical singing, while Gertrud went to a sculptor school. At the conservatory in Frankfurt Hildegund met the famous professor Paul Lohmann, who was one year older than her father and had lost an arm in WWI. They fell in love and stayed together until Paul’s death 1981.

Gertrud found the prospects of earning a living with sculpting too uncertain and switched to tailoring. Later she completed her education at the fashion school in Munich, where she met my father Walter Schmähling again in 1949. Walter’s family had been living in the same house as the Beckers in Aschaffenburg in the thirties and the kids had known each other. But Walter had been in Russia and France as a soldier and later a prisoner of war in England and the US. So their reunion came as a surprise to both of them. They married in 1952 and had a little boy (the author Mahendra) in 1956.

In the late fifties and all through the sixties and seventies Hildegund became an internationally acclaimed singing teacher and gave classes all over Europe.

Gertrud worked as a fashion designer for knitwear in Munich and brought up her boy. During holidays the sisters often met with their parents in Aschaffenburg.

After the death of her husband in 1981, Hildegund started the Lohmann-Foundation in Wiesbaden, which is still offering annual workshops for classical singing education. Gertrud lived with her husband in Munich.

getting old and death

At the turn of the millenium Hildegund was diagnosed with slowly growing dementia. She didn’t tell Gertrud about it, who was taking care of her dying husband in spite of becoming more and more fragile herself. After Walter’s death in 2005 both grew more and more lonely in their homes. In 2007 we had a little family reunion in Wiesbaden and at the end of it Gertrud decided to stay with her sister. For many years they slept together in a single bed and spent every moment of their life together. Hildegund had more and more difficulties to understand herself and the world around her and Gertrud’s eyesight and general physical condition worsened, but together they managed a simple life supporting each other. Every two month I visited them, checking that their needs were met and enjoying little trips with them in the vicinity.

In 2007 they waved goodbye to me in front of Hildegund’s house.

Posing at Lorelei, the famous cliff overlooking the Rhine.

Visiting the castle in Aschaffenburg. Both were very joyous to visit the places, where they had lived and played in their youth.

More and more verbal communication became difficult for the two sisters and conversations became a little dull. But when they played music, their eyes started shining like in the old days. I was particularly impressed by Hildegund’s capacity to read sheet music, when reading newspapers or letters had become impossible. Doctors confirmed to me that the part of the brain, which deals with music and general artistic activities, is often not much affected by Alzheimer’s disease, while the areas doing logical operations are shutting down more and more. If the caretakers create the space for artistic creativity, the patients can still have many joyful moments in their lives. Next is a video, which I took once, while visiting a former student of my aunt.

Hildegund’s 90th birthday. She had no idea, why we were celebrating, but nevertheless enjoyed the cake a lot.

Celebrating our last carnival together in Wiesbaden. Hildegund had broken an arm some weeks before, which made it really difficult for her to perform the quotidian routines. Gertrud lost her eyesight more and more and couldn’t help Hildegund much. Taking care of them in this situation was really a big challenge for me, but I still managed to buy those funny hats and some other carnival utensils, and we had a wonderful silly time together.

Mom’s 90th birthday. Shortly afterwards I had to take mom back to Munich as the two of them together couldn’t maintain a minimum of hygiene any longer and Gertrud wouldn’t allow the caretakers to get close to her sister. It was a tough decision, but Gertrud finally understood that she was unable to cope with their needs and that she needed a break.

Their last meeting. From 2015 I was taking care of mom in Munich and a professional caretaker looked after Hildegund in Wiesbaden. After some years in a state of happy not knowing Hildegund died in January 2019.

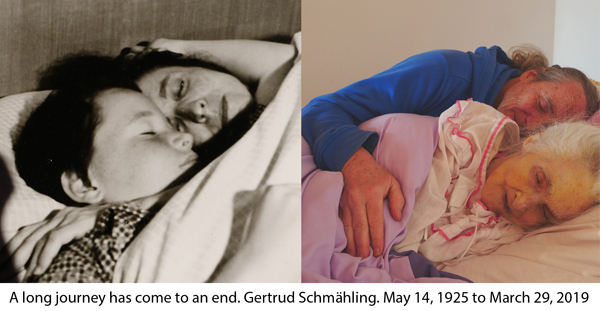

Gertrud stayed in her appartment in Munich until 2018, still playing the grand piano and having frequent walks with her caretakers. When her condition got worse I took her to my place in Walchensee. A few days before Gertrud’s death she already looked intensely into the beyond. A caretaker took this photo with her broken smart phone, while I was holding her.

Gertrud and Mahendra in August 1969 during a school holiday and on her final morning. A few days before I had looked through old photographs and saw how she had been holding and supporting me, when I was a kid. Before her last night the caretaker asked me to sleep by her side, as her breathing had been difficult because of a bronchitis. In spite of her heavy breathing I managed to sleep until 5am. Then I sat next to her, meditating and holding her hand. When the sun rose her breathing slowed down. I had my eyes closed. At some point the thought “there is no breathing sound at all from her” crossed my mind. I looked and she had stopped.