what is real?

In our quotidian life we tend to take us and the world around us as generally definable and defined phenomena, which we are perceiving objectively with our senses. Consequently we assume that the distinction between real and unreal or true and false can be made objectively based on our observations. However, modern sciences and mystics through the ages alike refute this concept and state clearly that on closer examination, there is no objective reality.

the mystical and the scientific understanding

Mystics claim, whatever we experience as our reality, is depending very much on the experiencer. And indeed, if we take the mystical approach and look, who is experiencing, we cannot come to an unambiguous conclusion. It’s impossible to define clearly with words, who we are. What we can do, however, is to exclude, what we are not, for example by stating

“You are never, what you think you are, and reality is never, what you think it is.”

Why? Because any thought that appears on our inner screen is a representation of a phenomenon or a group of phenomena of your sensual impressions and not the phenomenon or the group of phenomena itself. The mind never deals with the world out there directly, it is identifying and naming objects and thus creating internal symbols, words and sentences from the impressions it receives through the senses. The objectivity of our world is imaginary as we are only dealing with interrelating symbols within ourselves, which are forming thoughts and emotions, which are transformed into chains of thought in our brains. These processes are happening so fast, that we usually don’t realize their complexity and consequently we also fail to notice that each perceiver has his own unique version of an object.

The ancient yogis and rishis of the East understood the deceptive illusionary character of the world of phenomena through self observation and created the terms maya or samsara for the fleeting world of material and virtual objects.

In natural sciences on the other hand, we took the world as fairly static, solid and objectively real for many centuries . But since Einstein, Heisenberg, Bohr and the development of quantum physics the scientists and mystics have been coming very close to each other. Here are a few examples from the world of science, to make it clear, that there is also no absolute truth in science:

1. P.D. Ouspensky, a Russian mathematician and theosophist, who worked with George Gurdjieff, is giving a nice example from the field of mathematics:

1. P.D. Ouspensky, a Russian mathematician and theosophist, who worked with George Gurdjieff, is giving a nice example from the field of mathematics:

Anybody will agree that 1+1=2, right? If you, however, allow infinite as a value, you can make an equation ∞+1=∞, because infinite is always infinite, whether you add something or take something away. Then you take ∞ on both sides away and you’re left with 1=0 and the whole system comes crumbling down! That’s why the mathematicians have to exclude infinite and zero for certain operations, because math will not work otherwise. Which means, however, that mathematics is only true within a certain defined range and not absolutely, universally and indefinitely. When we look into realms beyond the mind the defined range is not valid any longer. Even Stephen Hawking, a famous contemporary genius of physics, admits in one of his books, that all of our scientific statements are not THE truth, but only auxiliary devices, as long as they give us a reasonable explanation and allow certain predictions about a phenomenon. Therefor there cannot be a guarantee that a formula, which works today, will also work tomorrow.

George Lakoff, one of the leading linguists of the last fifty years, comes to similar conclusions in his studies: “Mathematics turns out not to be a disembodied, literal, objective feature of the universe but rather an embodied, largely metaphorical, stable intellectual edifice constructed by human beings with human brains living in our physical world.” (Metaphors We Live By. 2003)

2. For a long time people believed in the flatness of the earth. Most of us laugh about it today, but for 15th century European citizens it was an experiential truth, that our planet is level like the surface of a frozen lake. Spheres were not rolling down to the left or right, when placed on the ice or an even board and generally in their own lives the concept of a flat earth worked perfectly well. So in fact the idea of the world as a sphere would have sounded rather weird to them. After Columbus, Kopernikus, Galilei and Newton the official views changed (after some trouble with the churches) and anybody, who still believed in a flat earth, was regarded as ignorant, even though from the perspective of the normal citizens nothing had changed. Even in our present day lives we are still partially thinking in terms of a geocentric plain, i.e. when we are using the words “sunrise” or “sunset” we are talking as if the sun would be circling around our planet, and architects are planning our houses on flat grounds as if the world would be flat. Also most distances are still calculated in a two dimensional flat surface model. Meanwhile Newton’s gravitational laws have been proven inaccurate to some extent by Einstein and his formulas are regarded as the real laws of physics. But one day somebody else will find even better equations …So, it is clear, we don’t have absolute values in science and all in all we can say that instead of looking at “true or untrue” we are dealing with a variety of concepts. Some of them allow us better predictions and others are allowing not so good predictions.

2. For a long time people believed in the flatness of the earth. Most of us laugh about it today, but for 15th century European citizens it was an experiential truth, that our planet is level like the surface of a frozen lake. Spheres were not rolling down to the left or right, when placed on the ice or an even board and generally in their own lives the concept of a flat earth worked perfectly well. So in fact the idea of the world as a sphere would have sounded rather weird to them. After Columbus, Kopernikus, Galilei and Newton the official views changed (after some trouble with the churches) and anybody, who still believed in a flat earth, was regarded as ignorant, even though from the perspective of the normal citizens nothing had changed. Even in our present day lives we are still partially thinking in terms of a geocentric plain, i.e. when we are using the words “sunrise” or “sunset” we are talking as if the sun would be circling around our planet, and architects are planning our houses on flat grounds as if the world would be flat. Also most distances are still calculated in a two dimensional flat surface model. Meanwhile Newton’s gravitational laws have been proven inaccurate to some extent by Einstein and his formulas are regarded as the real laws of physics. But one day somebody else will find even better equations …So, it is clear, we don’t have absolute values in science and all in all we can say that instead of looking at “true or untrue” we are dealing with a variety of concepts. Some of them allow us better predictions and others are allowing not so good predictions.

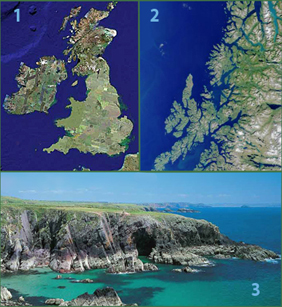

3. The coastline paradox: The measured length of the coastline of an island depends on the accuracy of the method, which we use to measure it. Since a landmass has features at all scales, from hundreds of kilometers in size to tiny fractions of a millimeter and below, there is no obvious size of the smallest feature that should be measured around, and hence no single well-defined perimeter to the landmass. For example the coastline of England can be measured from a satellite view (1), from an airplane view (2) or from actually observing the coast (3). Obviously we will have a problem with the last method as the level, frequency and power of the incoming waves are changing constantly. Various approximations exist when specific assumptions are made about minimum feature size.

3. The coastline paradox: The measured length of the coastline of an island depends on the accuracy of the method, which we use to measure it. Since a landmass has features at all scales, from hundreds of kilometers in size to tiny fractions of a millimeter and below, there is no obvious size of the smallest feature that should be measured around, and hence no single well-defined perimeter to the landmass. For example the coastline of England can be measured from a satellite view (1), from an airplane view (2) or from actually observing the coast (3). Obviously we will have a problem with the last method as the level, frequency and power of the incoming waves are changing constantly. Various approximations exist when specific assumptions are made about minimum feature size.

(excerpts from Wikipedia, full article see here: the coastline paradox)

If we are given the task of measuring such an object, we have to decide, which method is appropriate for our purpose. In case we want to make a bicycle trip along the coast of the main British island, we will probably not measure each stone on the shore, but rather we will measure the length of the roads in the vicinity of the coastline. The difficulty of multiple solutions arises not only in regard to the coastline of an island, but to many objects and processes in our world. In order to preselect from the infinite options, which we are facing in every moment of our lives, we are developing certain structures, routines and beliefs, which in turn influence our perception of reality.

Modern science confirms the view of the mystics, that we create our reality through our means of perception individually and subjectively. There might be a big overlap between your reality and your friends reality, and all societal groups have certain reality overlaps within their members, but ultimately your reality is unique. Each sentient being, each reflector of existence operates within their own reality and their own universe. If you take in account additionally that each being creates a new universe every moment (again with large overlaps from the universe of the moment before, but still fresh and new), it is not surprising that there is big chaos everywhere. In fact it is truly amazing that anything works at all! Yet, for reasons unknown, extremely unlikely and complex phenomena are continuously appearing (and disappearing) on our planet. And we actually have no chance to find out, why it’s all happening, as in the process of observation reality is already changing and being recreated. All we can say, is, that there is a something, a vague potentiality, an energy flow, which becomes a temporary actuality through being observed.

macrocosm and microcosm

Makena Beach on Maui

Grains of sand

Let’s look at our planet, where we walk around every day. Picture 1 is Makena beach on Maui with wonderful golden sand. Picture 2 is a little bit of this sand in a close up. There are about 2500 grains of sand in picture 2: One m² of the beach contains about 400 of our close up pictures, which is about one million grains of sand. The whole beach is about 80 000 m², so we have about 80 billion grains of sand on Makena Beach. Now extend your vision and imagine somebody collecting all the sand from all the beaches of the world on one big pile. What a huge collection of grains that would be! According to http://www.cosmotography.com/ researchers at the University of Hawaii have calculated this number by dividing the volume of an average sand grain by the volume of sand covering the Earth’s shorelines. The volume of sand was obtained by multiplying the length of the world’s beaches by their average width and depth. The number they calculated was seven quintillion five quadrillion (that’s 7 500 000 000 000 000 000 or 7.5 billion billion) sand grains!

With the image of this huge pile of sand in mind, let’s take a look into the sky. The next picture shows just a small portion of the night sky with the constellation Sagittarius, a bright part of the Milky Way and a lot more celestial bodies from our galaxy:

Part of the Milky Way

There are a lot of little white dots, the stars, visible with the naked eye. But many, many more, when looking through a telescope. 100 to 400 billion stars in our galaxy are the present estimate. Scientists have calculated that the number of stars in the known universe, which consists of approximately 2 trillion galaxies, is even bigger than the number of grains in our huge pile of sand. Even though the total amount of stars can be only a rough estimate, certainly a few more zeros must be added to our above number of sand grains.

Our earth is very, very tiny in comparison with the vastness of the universe and humans are even tinier.

But before you are overcome by depression and emotions of complete smallness, take a look at our pile of sand again and single out one grain only. Imagine taking a tiny chisel and hammer and splitting it up into it’s atoms, you will be getting an even larger number of atoms within one tiny grain than the number of stars in the universe.

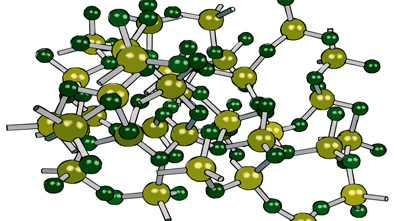

(Picture retrieved from enigmatics)

Our bodies are more than a million times bigger than a grain of sand. So we are incredibly big in relation to atoms and particles.

The picture shows a model of silicon dioxide molecules (SiO2), which are the main components of a grain of sand. We have no means of taking pictures of these structures, they are way beyond the range of electronic microscopes. But from experiments we know, that the infinitesimal structure should look somehow like this. The light green balls represent the silicon atoms, each one being connected with two of the smaller dark green oxygen atoms.

You may see now, how easy it is to feel superior or inferior just by choosing to compare the size of your body-mind-system to atoms or to stars.

But in our day to day life we don’t need to deal with galaxies or atoms (unless you are an astronaut or a nuclear physicist), instead we only have to deal with a range of medium sized phenomena ranging in most cases from a grain of sand to our sun, the area in which our practical lives are taking place. If it wouldn’t be so, life would be impossible. We can’t be simultaneously aware of whole the macrocosm, where a black hole might be gobbling up a whole galaxy millions of light years away, and of the microcosm in our body, where zillions of particles are madly dancing around almost unnoticed, while we are trying to get our jobs done here.

Our limited world

The limitation of perception is necessary for the functioning of our body-mind-system. We are living in a tiny corridor between the very small and the very big and only in this range life of sentient beings seems to be possible. We fade out or block information, which appears to be unnecessary or superfluous for us. The limits of our range of perception, which are created by the ongoing blocking processes, are changing constantly and are different for each being. So again – there is no objective reality and consequently no absolute right or wrong and good or bad. All phenomena including ourselves are relative.

All pictures by Mahendra, unless stated otherwise